Looking at search trends for “systems thinking,” I came across these videos of a 2004 roundtable at the 3rd International Conference on Systems Thinking in Management.

Pictured are Russ Ackoff, Margaret Wheatley, Michael Maccoby, Allenna Leonard, Michael Jackson, and Peter Checkland. Also on the videos but not pictured here are: Barry Silverman, John Sterman, Ian Mitroff, and moderator Vince Barabba.

A few snatches of the 3+ hours of conversation:

Video 1

Margaret Wheatley

My favorite definition of ethics is from the Catholic theologian David Steindl-Rast, who said, “Ethics is how we behave when we decide we belong together.”

Peter Checkland

The interesting thing about questions is always the assumptions behind them, which they take as given. … I rather like West Churchman’s [approach] when he said: “You are beginning to use a systems approach when you begin to see the world through the eyes of another.”

Ian Mitroff

The hard-soft [systems distinction] is one of the softest distinctions I’ve ever encountered in my life. … I don’t think we ought to spend the time on hard-soft. We ought to get rid of those silly dichotomies — which I think is one of the points of the systems approach, to get beyond those. Those really inhibit thought and creativity.

Video 2

Michael Jackson

To use mechanical models and biological systems to understand the nature of social systems can be a real mistake.

Michael Jackson

One of the weaknesses of the systems movement is that there are different silos that very few people try to break down.

Margaret Wheatley

One of the things that I’ve learned from biology and from being a student of living systems is that even this notion of separation and individualism is not a biological concept. You can’t go into the living world with a notion of independent actors and see anything that’s useful.

Michael Maccoby

We are the only animal that needs meaning to survive.

Peter Checkland

The worldview of the 1950s is that systemicity lies in the world — the world is an interacting set of systems, some of which don’t work very well, and we can come along and make them work better. … We had to abandon systems engineering when we failed to be able to apply it in soft, messy, management problem situations. … [Instead] we work with the notion that people create meaning together and can reach accommodations. …

When we asked ourselves: “what was the worldview we had now developed?” we saw that it was totally different from the 1950s worldview we had started from. … The 1950s view of systemicity is that it lies in the world, and you come along and engineer the systems in the world to be better. Our process involved us to take a phenomenological stance, philosophically, and an interpretive stance, sociologically. We gave up on thinking of the world as containing systems. … What we were doing was putting the notion of systems into the process of dealing with the world, the process of inquiry into the world.

Ian Mitroff

I don’t believe in the terms objective and subjective. They ought to be replaced by the term “judgement.” We differ in out judgements.

Michael Jackson

I think it’s incumbent upon us all the time to justify why we think working or operating in a systems way is any better to operating in a way that some people might call common sense, or based upon history, or based upon analysis. We’ve got to demonstrate that working in a systems way actually brings better results.

Peter Checkland

In teaching these ideas, you do find very different propensities to understand them among different students. We don’t correlate with ordinarily measured intelligence. … On our master’s course, over thirty years, most of the distinctions went to women, though we never had more than 40 percent of women in any one year in the course. So there’s anecdotal evidence that women are more inclined to think systemically or holistically.

Michael Maccoby

You can’t understand yourself without systems thinking. You can’t do it. … We [tend to] think our particular values and personalities are human nature.

Russ Ackoff

You will never get support for a plan from people who didn’t participate in making it.

Vince Barraba

The key to the [1980 census] program was that we published the assumptions under which the decision would be made. We published them in the Federal Register and asked people to comment on the assumptions, not on the decision. … It was not a well received decision. … But the final [ruling] of the appellate courts was that the process the Census Bureau used was neither capricious nor arbitrary.

Watch >>

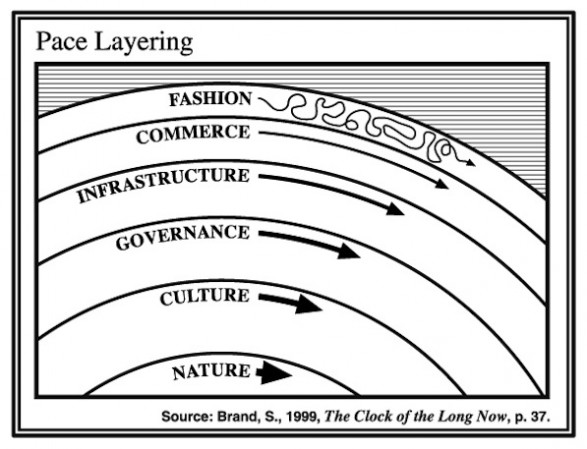

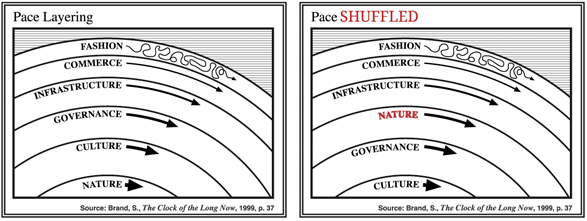

I’ve written before about Stewart Brand’s pace layers — a nifty hierarchy that orders rates of change from fast to slow, system by system: fashion, commerce, infrastructure, governance, culture, and nature.

I’ve written before about Stewart Brand’s pace layers — a nifty hierarchy that orders rates of change from fast to slow, system by system: fashion, commerce, infrastructure, governance, culture, and nature.

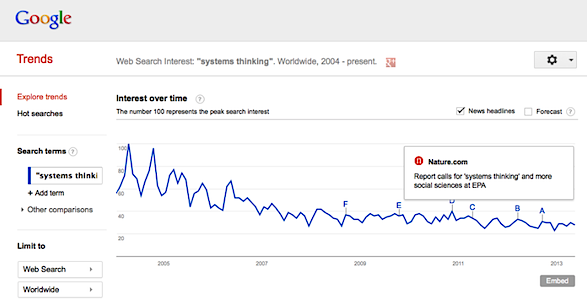

Two mysteries in this Google trends search for the phrase “

Two mysteries in this Google trends search for the phrase “