In the 2009 World Bank report, “A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change,” Elinor Ostrom challenged the notion that a global atmosphere requires global action.

Given the complexity and changing nature of the problems involved in coping with climate change, there are no “optimal” solutions. … The advantage of a polycentric approach is that it encourages experimental efforts at multiple levels, as well as the development of methods for assessing the benefits and costs of particular strategies adopted in one type of ecosystem and comparing these with results obtained in other ecosystems.

This polycentricity is playing out slowly, of course, at governance levels from nations to provinces/states to cities.

Recently, University of Oregon’s Ronald Mitchell circulated a request for scholarly writings on multi-level governance. Ron wrote:

I am trying to advise a student working on why a country might be reluctant in assuming international climate obligations even while it’s subnational units (provinces/states, cities) are taking action on climate change. Any suggested of literature that would point in the direction of good theorizing on the factors that might explain such variation would be appreciated.

Among the responses, here are four abstracts that caught my eye.

Zelli, F. (2011). The fragmentation of the global climate governance architecture. WIREs: Climate Change, 2(2), 255-270.

The term fragmentation implies that policy domains are marked by a patchwork of public and private institutions that differ in their character, constituencies, spatial scope, subject matter, and objectives. While the degree of fragmentation varies across issue areas and their respective architectures, global climate politics is characterized by an advanced state of institutional diversity. In recent years, scholars have increasingly addressed this emerging phenomenon of international relations. The article finds that the predominant focus of these studies has been on dyadic overlaps, i.e., interlinkages between two institutions, and less on the overarching level of entire architectures and their degree of fragmentation. This goes in particular for research on the global climate change architecture. Many studies have attended to the relationship between the United Nations climate regime and other institutions: multilateral technology partnerships, regimes regulating other environmental domains like ozone or biological diversity, and regimes from non-environmental issue areas like the world trade regime. However, a cross-cutting account of these overlaps which addresses the overall implications of institutional fragmentation on climate change is still missing. As possible areas for further research the article identifies: consequences of fragmentation (e.g., a new division of labor or increased inter-institutional conflict), fragmentation management and conditions of its effectiveness; theory-driven analyses on the reasons of fragmentation within and across policy domains.

Hochstetler, K., & Viola, E. (2012). Brazil and the politics of climate change: beyond the global commons. Environmental Politics, 21(5), 753-771.

Assessing the changing role of the emerging powers in global climate change negotiations, with special attention to Brazil, we ask why they have agreed to voluntary reductions at home without formalising those commitments in ways that might persuade other large emitters to make similar binding commitments. We argue that for very large emitters, the climate issue does not evince the ‘global commons’ logic often attributed to it. Instead, since their actions can directly affect climate outcomes alone or in small groupings, large emitters are more responsive to domestic cost-benefit calculations, making international commitments based on shifting interest group pressures at home. In Brazil, a coalition of ‘Baptists and bootleggers’ found principled and interest-driven reasons to support new climate commitments after 2007.

Fisher, D. R. Forthcoming. Understanding the relationship between sub-national and national climate change politics in the United States: Toward a theory of boomerang federalism. Environment & Planning C, Government and Policy.

This paper looks at how sub-national policies in the United States are interacting with policymaking at the federal level to address the issue of global climate change. It focuses on a coordinated attempt to get the national government to fund local efforts to address climate change. Although local climate initiatives in the US were successfully translated into a national policy to support these local efforts, their implementation through hybrid arrangements that are being formed between business and local governmental actors will potentially create additional challenges to federal policymaking. I introduce the notion of boomerang federalism, which builds on the extant research on federalism and vertical policy integration, to explain the process through which local efforts mobilize initiatives at the national level that, in turn, provide support for the local initiatives themselves. Reviewing the implementation process of this effort, I discuss the ways that businesses are working alongside local governments to address climate change.

Harrison. K. Forthcoming. Federalism and Climate Policy Innovation: A Critical Reassessment. Canadian Public Policy.

This article argues that the prospects for US state and Canadian provincial climate policy innovation and diffusion are limited in several respects. Subnational climate leaders tend already to be the cleanest states and provinces, and even they have been strategic in the sectors they regulate and the instruments they employ. In some cases, this selectivity appears to be motivated by opportunities to shift compliance costs to other states. Efforts to pool risks through state and provincial collaboration also are flagging in the wake of the Canadian and US federal governments’ failure to adopt nation-wide policies to level the playing field.

See also: Ronald Mitchell: Reasons for climate optimism.

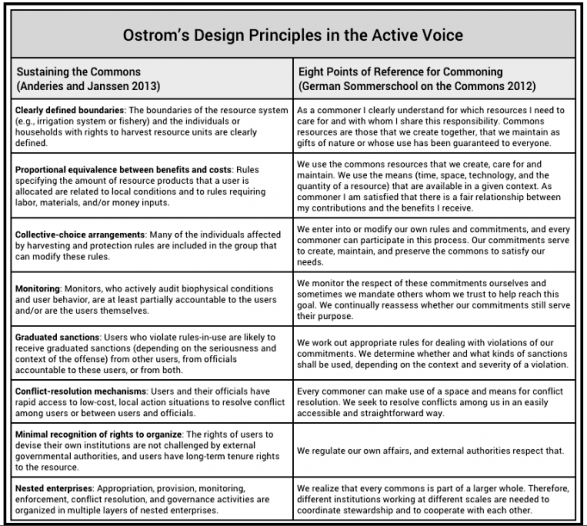

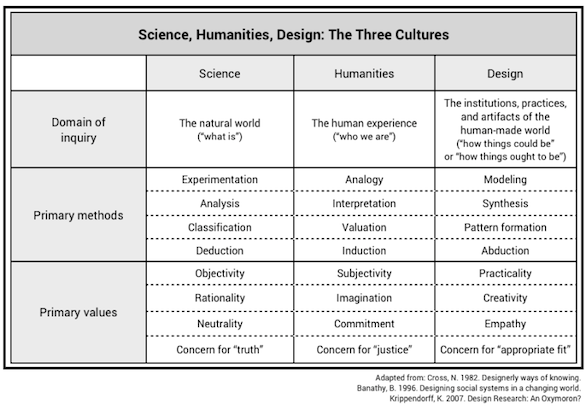

Are there designerly ways of knowing — distinct from the ways of the sciences and humanities? I’ve explored these questions in the writings of Béla Bánáthy and Nigel Cross, from whom I adapted the table above.

Are there designerly ways of knowing — distinct from the ways of the sciences and humanities? I’ve explored these questions in the writings of Béla Bánáthy and Nigel Cross, from whom I adapted the table above.