What do you do when your world has changed? Hold on to the past? Adapt to the new? According to Bayesian cognitive theory, we’re always doing a bit of both: holding onto prior beliefs, while adapting to incoming signals.

My interest here is in the Bayesian model of cognition — the “Bayesian brain” — and in what it might mean for understanding climate change. Inextricably coupled with the theory of the Bayesian brain are the statistical methods of Bayesian inference. While the statistical theorems date back centuries, the cognitive science is recent. The methods are a hot topic, the model not so much, yet.

Champion of Bayesian statistics Nate Silver discussed climate in a chapter of his 2012 book, The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail — but Some Don’t, to which climatologist Michael Mann responded with a friendly-yet-scathing critique.

The exchange left me a little puzzled. Sure, there were oddities and errors in Silver’s chapter, the ones that Mann detailed and more. Still, I wondered about Mann’s seemingly categorical dismissal of Silver’s Bayesian approach (see update below), and I noted that Dan Kahan, known for his research on cultural cognition, had a similar reaction. At the same time, I also noticed that neither Silver nor Kahan referenced the recent Bayesian cognitive research.

The relaunch of Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, which I wrote about last time, has me looking at this topic again. In this post, I’ll test out some pattern recognition and seek your feedback.

Bayesian Brain

I’ll begin with expert introductions to the cognitive field by Chris Frith and Stanislas Dehaene; later on, I’ll also reference a couple of talks by Karl Friston.

“[O]ur brain is a Bayesian machine,” wrote Frith in 2007’s Making Up the Mind: How the Brain Creates our Mental World — a lucid account of the research narrative.

[O]ur brain is a Bayesian machine that discovers what is in the world by making predictions and searching for the causes of sensations. … Our brains build models of the world and continuously modify these models on the basis of the signals that reach our senses.

Dehaene gave a concise summary of the cognitive research in response to the 2008 Edge question (“The Brain’s Schrödinger’s Equation”):

For many theoretical neuroscientists, it all started twenty five years ago, when John Hopfield made us realize that a network of neurons could operate as an attractor network, driven to optimize an overall energy function which could be designed to accomplish object recognition or memory completion. Then came Geoff Hinton’s Boltzmann machine — again, the brain was seen as an optimizing machine that could solve complex probabilistic inferences. Yet both proposals were frameworks rather than laws. Each individual network realization still required the set-up of thousands of ad-hoc connection weights.

Karl Friston, from UCL in London, has presented two extraordinarily ambitious and demanding papers in which he presents “a theory of cortical responses”. Friston’s theory rests on a single, amazingly compact premise: the brain optimizes a free energy function. This function measures how closely the brain’s internal representation of the world approximates the true state of the real world. From this simple postulate, Friston spins off an enormous variety of predictions: the multiple layers of cortex, the hierarchical organization of cortical areas, their reciprocal connection with distinct feedforward and feedback properties, the existence of adaptation and repetition suppression… even the type of learning rule — Hebb’s rule, or the more sophisticated spike-timing dependent plasticity — can be deduced, no longer postulated, from this single overarching law.

The theory fits easily within what has become a major area of research — the Bayesian Brain, or the extent to which brains perform optimal inferences and take optimal decisions based on the rules of probabilistic logic. Alex Pouget, for instance, recently showed how neurons might encode probability distributions of parameters of the outside world, a mechanism that could be usefully harnessed by Fristonian optimization. And the physiologist Mike Shadlen has discovered that some neurons closely approximate the log-likelihood ratio in favor of a motor decision, a key element of Bayesian decision making. My colleagues and I have shown that the resulting random-walk decision process nicely accounts for the duration of a central decision stage, present in all human cognitive tasks, which might correspond to the slow, serial phase in which we consciously commit to a single decision. During non-conscious processing, my proposal is that we also perform Bayesian accumulation of evidence, but without attaining the final commitment stage. Thus, Bayesian theory is bringing us increasingly closer to the holy grail of neuroscience — a theory of consciousness.

Dehaene, in his 2014 book: “The hypothesis that the brain acts as a Bayesian statistician is one of the hottest and most debated areas of contemporary neuroscience.”

Climate Change

Turning to the topic of climate, it’s illustrative to compare two examples of Bayesian inferential reasoning: one from Nate Silver and the other from physicist Sean Carroll.

Silver, in the climate chapter of Signal and Noise:

Suppose that in 2001, you had started out with a strong prior belief in the hypothesis that industrial carbon emissions would continue to cause a temperature rise. … But then you observe some new evidence: over the next decade, from 2001 through 2011, global temperatures do not rise. … Under Bayes’s theorem, you should revise your estimate of the probability of the global warming hypothesis downward; the question is by how much.

Carroll, in the Q&A to this 2013 talk (~1:01:50):

Q: Can you apply what you know about physics to what we might know about the future and climate?

Sean Carroll: If I were responsible, I would just say ‘no.’

Climate is very, very complicated. The question we should think about in terms of climate change is not a physics question. It’s a Bayesian probability question.

That is to say, I am not an expert on climate. My knowledge of how electrons and gravity work is of absolutely no use in understanding how the climate works. I know how the greenhouse effect works. But I also appreciate that there’s a lot more to the climate than just the greenhouse effect, so I wouldn’t trust my own judgement.

The reason I say Bayesian probability is because the Reverend Thomas Bayes gave us a way of assigning the probability that a certain theory is correct, in the presence of certain data, certain pieces of information.

Now I might a priori say: ‘I don’t know what’s happening with the climate.’ Then someone shows me the graph of temperature that goes like this [up steeply], and someone shows me the other graph of the carbon dioxide that goes like this [also up steeply], and my meager physicist’s mind would say: ‘You know I bet putting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is warming the Earth.’

Then, I look at all the climate scientists in the world, and they tell me that putting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is warming the Earth. That’s another piece of data.

And it’s overwhelmingly clear at this point in time, from all the information that we have — not because I’m a scientist, but because I’m a human being — that we human beings are making the Earth much, much warmer. And it’s potentially very disastrous, and we should stop doing it.

Needless to say, I agree with Carroll on this last point.

Pattern Recognition

Nate Silver and Sean Carroll started with similar questions, basically: Are humans causing climate change? But they selected different signals and came to different conclusions. Silver followed year-by-year global surface temperatures, while Carroll referenced climate science research findings and the scientific consensus. The problem with Silver’s choice of signals, Michael Mann wrote, is that yearly temperatures are not the same as climate. Scientific explanations for recent global temperatures point elsewhere, to the ocean absorption of heat. Plus there is the issue of what dates one uses for such an analysis.

At the same time, Silver’s and Carroll’s approaches have much in common. Both advocate for Bayesian reasoning. Silver sees it as “essential to scientific progress.” Likewise, Karl Friston describes his own Bayesian reasoning as “hypothesis testing in a Popperian sense” (~7:45). Silver and Carroll each seek to help their audiences get better at making sense of the world. I aspire to no less.

Still, if the Bayesian model of brain function is accurate, advocating for Bayesian reasoning becomes somewhat paradoxical. One might advocate for statistical quantification (Silver) or for a particular set of signals (Silver and Carroll). But according to the cognitive theory, Bayesian reasoning itself is simply what we do — inescapably what we all do.

Moreover, Bayesian reasoning hardly guarantees scientific conclusions. As other cognitive research shows, people have plenty of biases. One might hold Bayesian prior beliefs that are like one of the worldviews in Dan Kahan’s cultural theory-type research. Or one’s Bayesian signal selection might depend on the types of credibility calculations described in Arthur Lupia’s research.

In the end, Michael Mann emphasized, the greenhouse effect and other laws of physics are “true whether or not you choose to believe them.” Meanwhile, how individuals come to believe a truer understanding of the physical world — or fail to do so — is exactly what a Bayesian model of cognition, or something like it, might be used to explain.

To my mind, this bridge from subjective to objective is the power of the Bayesian approach. Metaphorically, it’s a feature not a bug. “What we’re doing, in quite a fundamental way,” declared Karl Friston (~30:30), “is coupling the immaterial to the material.”

In recent years, there has been a lot of discussion about climate-related cognition and communication: ways that people understand climate and ways of engaging others in conversations about climate. One notable venue has been the Sackler Colloquia on the Science of Science Communication (I and II). A critical piece that’s been missing from these discussions, if I’m not mistaken, is a cognitive model of how each of us updates his or her understandings over time. That’s what researchers on the Bayesian brain seek to provide. And that would be a very valuable thing.

References:

- Carroll, S. 2013. Purpose and the Universe. 2013 American Humanist Association Annual Conference.

- Dehaene, S. 2008. The Brain’s Schrödinger’s Equation. Edge.

- Dehaene, S. 2014. Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. Viking Adult.

- Friston, K. 2014. Consciousness and the Bayesian Brain. Joseph Sandler Research Conference 2014.

- Friston, K. 2014. Discussion. Joseph Sandler Research Conference 2014.

- Frith, C. 2007. Making Up the Mind: How the Brain Creates our Mental World. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kahan, D. 2012. Wisdom from Silver’s Signal & Noise, Part 2: Climate Change & the Political Perils of Forecasting Maturation. Cultural Cognition Project.

- Lupia, A. 2012. Why We Can’t Trust Our Intuitions: Communication as a Science. Sackler Colloquia, US National Academy of Sciences.

- Mann, M. 2012. FiveThirtyEight: The Number of Things Nate Silver Gets Wrong About Climate Change. Huffington Post.

- Nuccitelli, D. 2013. What has global warming done since 1998? Skeptical Science.

- Sackler Colloquia on the Science of Science Communication I and II. 2012-13. US National Academy of Sciences.

- Silver, N. 2012. The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail — but Some Don’t. Penguin Press.

- Silverman, H. 2010 / 2013. Climate and Cultural Theory. Solving for Pattern.

- Tamino. 2014. Global Temperature: the Post-1998 Surprise. Open Mind.

UPDATE: response from Michael Mann

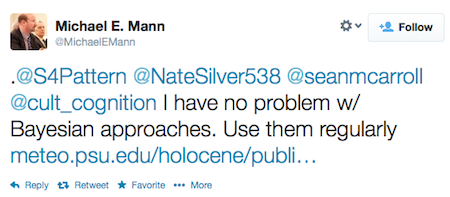

A few stories I came across recently have me thinking about the challenges of organizational learning — in this case, with respect to the U.S. military.

A few stories I came across recently have me thinking about the challenges of organizational learning — in this case, with respect to the U.S. military.

Mahatma Gandhi looked up from his spinning wheel as an attendant read aloud from a letter: “Dear Mr Gandhi: We regret we cannot fund your proposal because the link between spinning cloth and the fall of the British Empire was not clear to us.”

Mahatma Gandhi looked up from his spinning wheel as an attendant read aloud from a letter: “Dear Mr Gandhi: We regret we cannot fund your proposal because the link between spinning cloth and the fall of the British Empire was not clear to us.”