Which factor has a bigger influence on climate concerns in the U.S — extreme weather events, scientific information, mass media coverage, media advocacy, or elite cues?

This question was asked by sociologists Robert Brulle, Jason Carmichael, and J. Craig Jenkins in the January 2012 paper, “Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010” (pdf).

Brulle described their findings in an October 2012 PBS Frontline interview:

Media coverage on climate change peaked in 2007 and 2008, and it’s been declining back to about 2002 levels in the current time. So you see a great big sort of hump as public opinion went up, media coverage went up.

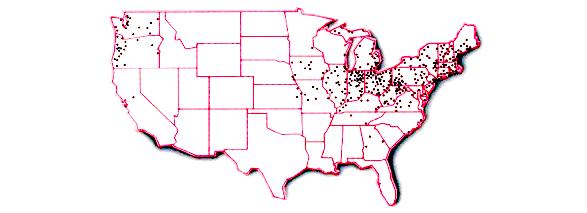

What we were able to explain is, what drives media coverage? And we looked at a number of factors. Weather disasters, nope — doesn’t affect public opinion at the national level. It might affect that locality, but you’ve got a lot of weather all over the place in the United States, so weather has had no significant impact on climate change public opinion.

Scientific information promulgation about climate change has done nothing but go up and up and up, and climate change public opinion has gone up and down. So while information increases, public opinion goes up and down. There is no statistical relationship between providing information about climate change and levels of public concern.

I know that that’s a big blow to a lot of people in the climate change communication field, but that’s what we found: no relationship.

… One major factor that drove a lot of concern about climate change was Al Gore’s movie, An Inconvenient Truth. That really got a lot of media coverage. It put it into the public agenda in a very big way.

It wasn’t the number of people that saw it, that actually went to the movie theater, but it was the media coverage pump that climate change got in response to Al Gore’s movie. We know that Al Gore’s movie drove that pump, and so we know that that movie had a really significant impact on climate change concern in the United States.

The other thing that has a lot of impact are what we call “elite cues.” People have certain ideological beliefs, and they look to opinion leaders on matters that they don’t have direct experience [with] for guidance. So people that trust and listen to Rush Limbaugh hear [him] say that global climate change is a hoax. “Well, I trust Rush; I believe him.” And so their opinion follows it, and you call them up and you say, “What do you think about climate change?,” and they say, “I think it’s a hoax.” Or they believe Al Gore and know it’s real. They follow their ideological leaders, or their thought leaders have this big, big impact, so what we call elite cues.

From the paper:

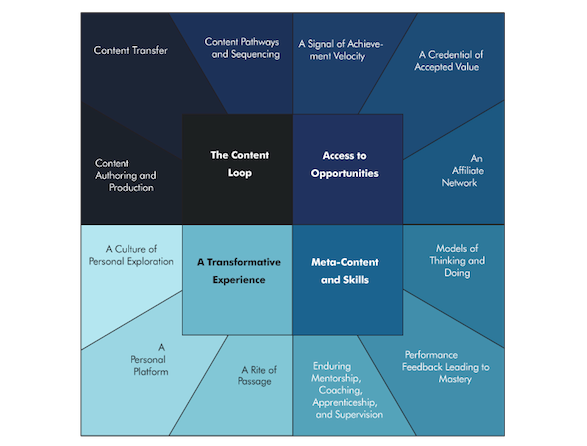

To test the influence of these five factors and the control variables, we developed a series of measures of the independent variables, as described below. There are six different categories of variables.

1. Extreme Weather Events. To capture weather extremes, we use four measures of weather variability from the NOAA Climate Extremes Index (Gleason et al. 2008).

- Overall Climate Extremes Index

- Extremes in Maximum Temperature—percentage of United States with maximum temperatures much above normal

- Extremes in 1-Day Precipitation—Twice the value of the percentage of the United States experiencing extreme (more than two inches) one-day precipitation events

- Drought Levels—percent of U.S. in severe drought based on the PDSI

2. Scientific Information. We used three measures to capture the dissemination of scientific information about climate change:

- The number of articles about climate change in the refereed journal Science

- Popular scientific magazine coverage of climate change—the number of stories on climate change in 15 major popular scientific magazines

- Release of major scientific assessments of climate change

3. Mass Media Coverage. We constructed a mass media index based on an additive index of three measures:

- Number of stories on climate change on the nightly news shows of the major broadcast TV networks (NBC, CBS, ABC)

- Number of stories on climate change in The New York Times

- Number of stories on climate change in Newsweek, Time, and U.S. News and World Report

4. Media Advocacy. To capture media advocacy efforts, we utilized three measures:

- Number of stories on climate change in 12 major environmental magazines

- Number of stories on climate change in 6 conservative magazines

- Number of New York Times mentions of An Inconvenient Truth

5. Elite Cues. To capture elite cues, we include three measures?

- Congressional press release statements on climate change issued by Republicans and Democrats

- Senate and House roll call votes on climate-change bills identified in the League of Conservation Voters (LCV) National Environmental Scorecard

- Number of Congressional hearings on climate

6. Control Variables. We added four control variables that have been hypothesized to influence public concern about the environment:

- Unemployment rate

- Gross Domestic Product

- War deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan

- Price of oil

Worth noting: Media coverage on cable news like FOX was not included.

From the conclusion:

Overall, the analysis explains nearly 80% of the variance in U.S. public concern over climate change. … The major factors that affect levels of public concern about climate change can be grouped into three areas. First, media coverage of climate change directly affects the level of public concern. … The most important factor in influencing public opinion on climate change, however, is the elite partisan battle over the issue. … As noted by McDonald (2009:52 pdf) “When elites have consensus, the public follows suit and the issue becomes mainstreamed. When elites disagree, polarization occurs, and citizens rely on other indicators, such as political party or source credibility, to make up their minds.” This appears to be the case with climate change.