“Let us suppose,” wrote Neil Postman in his final (1999) book, Building a Bridge to the 18th Century: How the Past Can Improve Our Future, “as Jefferson did, and much later John Dewey, … that the best way for citizens to protect their liberty is for them to be encouraged to be skeptical.”

How would such critical thinking be taught? Postman described five suggestions (which I’ve compressed, without ellipses):

Teach children something about the art and science of asking questions.

Question-asking is the most significant intellectual tool human beings have. What will happen if a student, studying history, asks, ‘Whose history is this?’ What will happen if a student, being given a set of facts, asks, ‘What is a fact? How is it different from an opinion? And who is the judge?’What happens, of course, is that students not only learn ‘history’ and ‘facts’ but also learn where these things come from and why. Such learning is at the heart of reasoning and its product, skepticism.

Give logic and rhetoric a prominent place in the curriculum.

These subjects sometimes go by different names today — among them, practical reasoning, semantics, and general semantics. They are about the relationship between language and reality; they are about the differences between kinds of statements, about the nature of propaganda, about the ways in which we search for truths, and just about everything else one needs to know in order to use language in a disciplined way and to know when others aren’t.Teach a scientific outlook.

The science curriculum is usually focused on communicating the known facts of each discipline without serious attention to the history of the discipline, the mistakes scientists have made, the methods they use and have used, or the ways in which scientific facts are either refuted or confirmed.Teach ‘technology education.’

Forty-five million Americans have already figured out how to use computers without any help whatsoever from the schools. If the schools do nothing about this in the next ten years, everyone will know how to use computers. But what they will not know, as none of us did from everything from automobiles to movies to television, is what are the psychological, social, and political effects of new technologies.Provide our young with opportunities to study comparative religion.

Such studies would promote no particular religion but would aim at illuminating the metaphors, literature, art, and expression of religious expression itself.I suspect readers have noticed that my five suggestions do not include history as a subject to be studied. In fact, I regard history as the single most important idea for our youth to take with them into the future. I call it an idea rather than a subject because every subject has a history, and its history is an integral part of the subject. History — we might say — is a meta-subject.

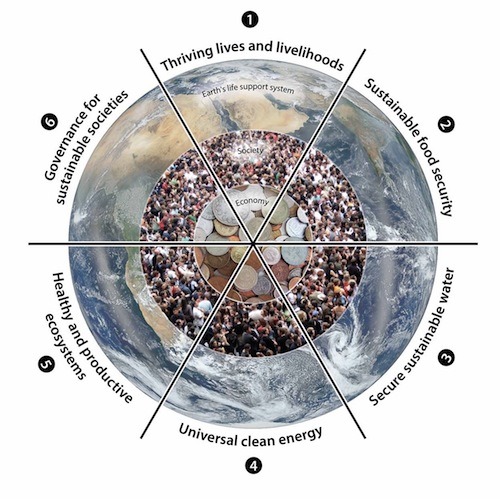

This morning, I mentioned Stockholm Resilience Center executive director

This morning, I mentioned Stockholm Resilience Center executive director