“There is a need for a paradigm shift in the way publicly owned irrigation systems are managed,” writes Aditi Mukherji in a World Water Day (March 22nd) post (“Cooperation by water users: Does it work?”).

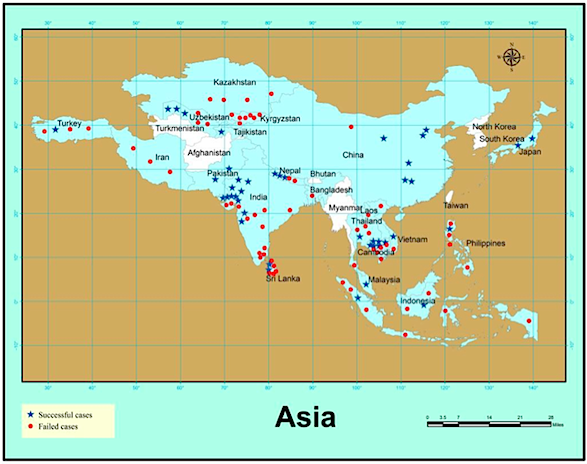

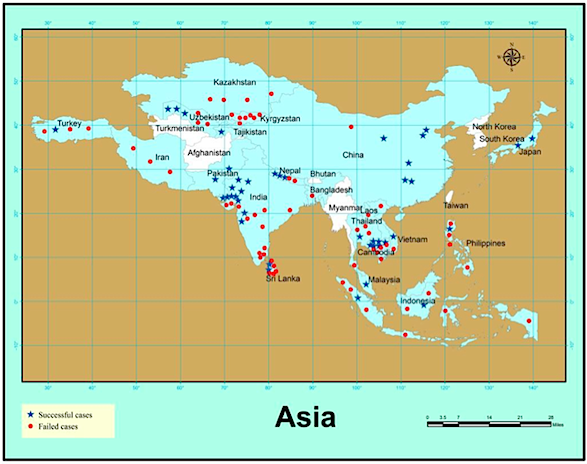

She summarizes a review of 108 cases of irrigation management transfer (IMT) and participatory irrigation management (PIM) across 20 countries in Asia. It’s the broadest meta-analysis to date of efforts to foster local governance of modern irrigation systems through water users associations (WUAs).

Think analogously, in a U.S. context, of irrigation systems like the Columbia Basin Project in southeast Washington state, built by the Bureau of Reclamation from 1945 to 1955 and then transferred to local irrigation district governance in 1969.

Of the 108 cases, the authors rate 42 as successful and 66 less so, with findings mapped out as below.

Mukherji, also lead author on the review, was the first recipient of the recently inaugurated Borlaug Field Award, endowed by the Rockefeller Foundation. The Agriculture and Ecosystems blog is a project of the CIGAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems, and CGIAR is the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, a global amalgamation of 15 research centers, along with funding and other supporting entities.

Mukherji, also lead author on the review, was the first recipient of the recently inaugurated Borlaug Field Award, endowed by the Rockefeller Foundation. The Agriculture and Ecosystems blog is a project of the CIGAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems, and CGIAR is the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, a global amalgamation of 15 research centers, along with funding and other supporting entities.

Some key pieces from the review paper (“Irrigation reform in Asia: A review of 108 cases of irrigation management transfer,” pdf).

Critique of IMT:

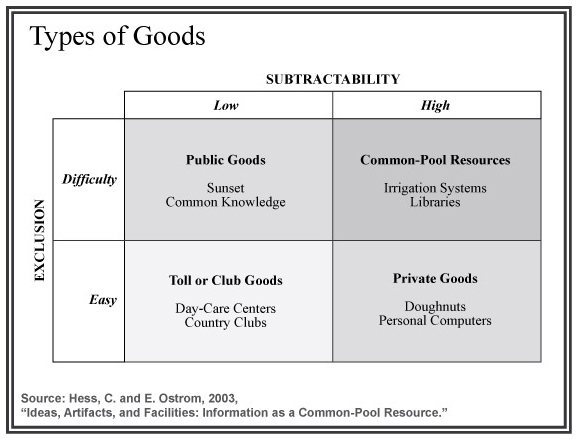

There are three theoretical assumptions behind IMT, assumptions, that we contend, have not been unpacked properly. First, it is assumed that because traditional self governed irrigation systems have endured, therefore, WUAs in modern canal systems too will. Second, it is thought that most of these public systems have potential to be financially and economically viable, but government management is not the ideal way to achieve this. Third, it is assumed that resource users (i.e. the farmers) are ideally suited to manage these systems, because they have the largest stake in long term sustainability of the resource.

Definition of success:

[W]e define IMT/PIM intervention as successful when there is a marked improvement after transfer or transferred systems fare better than non-transferred ones because users receive adequate and reliable supply of water at reasonable and affordable costs over a sufficiently long period of time enabling them to increase their crop production, productivity and incomes.

Factors supporting successful projects:

[W]e find that active farmers’ participation (Japan), small size of systems and presence of rich social capital (Nepal), long drawn involvement of NGOs (Sri Lanka and India) and provision of correct incentives to the irrigation official and farmers (China) led to success. The important point here is that all these are hard or costly to replicate, except perhaps the provision of right incentive structure.

Conclusion:

This review of 108 case studies shows that IMT/PIM is far from a panacea to all problems and that there is no magic formula for crafting successful WUAs. Our review of evidence from some decades of experiments is far from encouraging; by far the most celebrated experiments—catalyzed, sustained and micro-managed by NGO’s with the help of unreplicable quality and scale of resources and donor support (e.g. Gal Oya in Sri Lanka, Baldeva LBMC in Gujarat) report only modest gains in terms of performance and sustainability, leading researchers to demand ‘reform of reforms’.

On the Columbia Basin Project, see: “Irrigation Management Transfer in the Columbia Basin, USA: A Review of Context, Process and Results” (pdf), by Douglas Vermillion.

Mukherji, also lead author on the review, was

Mukherji, also lead author on the review, was