Mahatma Gandhi looked up from his spinning wheel as an attendant read aloud from a letter: “Dear Mr Gandhi: We regret we cannot fund your proposal because the link between spinning cloth and the fall of the British Empire was not clear to us.”

Mahatma Gandhi looked up from his spinning wheel as an attendant read aloud from a letter: “Dear Mr Gandhi: We regret we cannot fund your proposal because the link between spinning cloth and the fall of the British Empire was not clear to us.”

That’s a cartoon in Michael Quinn Patton’s 2011 book, Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use (reprinted from folks at Search for Common Ground Indonesia).

Snarky perhaps, but also incisive.

Traditional program evaluation models — accounting for programmatic inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts — are invaluable. They are, however and by definition, not developmental: not amenable to ongoing iteration, and not designed for encouraging innovation.

The accountability of developmental evaluation, then, Patton says in the talk linked below, “is that something gets developed — and that something has value, is making a difference, generates learning.”

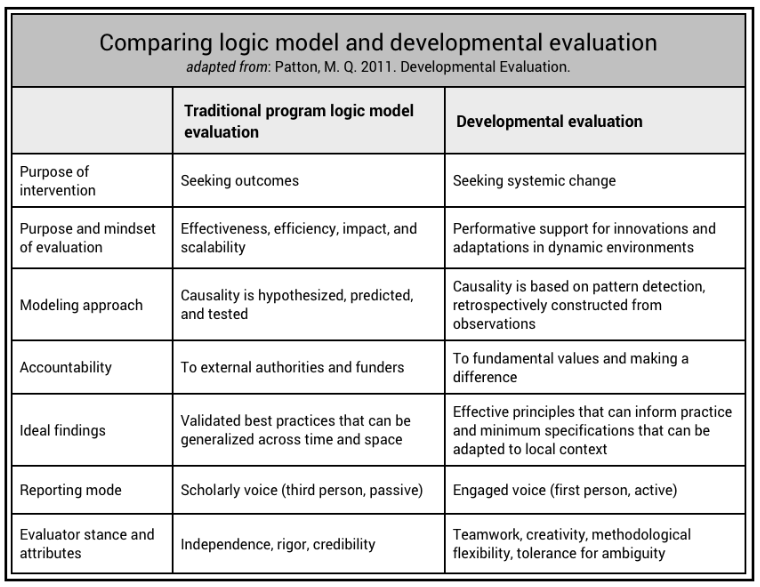

I’ve adapted and abbreviated the table above from the book’s extensive comparison of the two approaches. Recently, I caught a 2013 webinar by Patton, hosted by Social Innovation Generation (SiG), for which he also shared his slides.

One thing I’ve wondered about, when it comes to types of evaluation, is the contention that the developmental approach merely serves “niche” activities.

This statement is in Patton’s book, and the SiG host reiterated it in the webinar introduction. (“DE is not for every evaluation situation. Indeed, the niche is quite specific.”) It also came up implicitly in the webinar Q+A, when Patton was asked about whether the developmental approach is a good fit for existing organizations.

Here’s his response (~53:00):

When I work with organizations, I don’t recommend that all of their evaluation become developmental evaluation. Most organizations are implementing models. Most funding is funding models. We still have a model mentality.

The place to look for developmental evaluation, within an ongoing organization, is wherever the leadership is talking about things like innovation [and] systems change. Not for everything that they do. But in fact most organizations have some area in which, while they do business as usual, they also want to do some innovation.

I find that the business world totally gets this. Most major corporations do R&D work, and R&D — venture capital work, trying new things out, developing things — is what DE is in the nonprofit, voluntary sector. DE is the R&D function. It’s where you try things out.

Even in government, you wouldn’t expect and no one could run a government on DE principles. Nobody would ever get elected saying, ‘I’m not sure where we’re going to go. Trust me. We’ll adapt as we go along.’

But where there are pockets of government — in provinces and communities — where people are saying, ‘We don’t know the solution to this problem. We’ve tried out lots of things. We want to engage people in the community in coming up with their own innovative solutions.’ That’s the place to do DE.

So you look for those pockets of innovation, places where systems change is being talked about. It’s not the whole organization. It’s the place where people are serious about innovation and systems change.

That sounds to me like a pretty big niche. And getting bigger.