[Update: 20AUG2013 posted revised table at top. See update here.]

Are there designerly ways of knowing? Does the design mode of inquiry depend on distinct methods and values? How might design ability be developed?

Nigel Cross, emeritus professor of design studies at The Open University, has been exploring these questions since the 1970s, in a long list of publications.

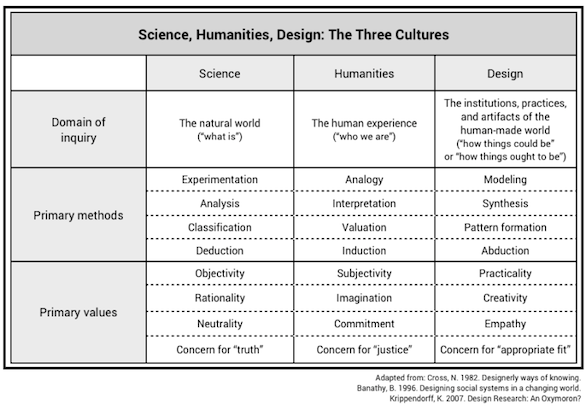

I adapted this table from the writings of Cross and from a similar table by Béla Bánáthy in Designing Social Systems in a Changing World.

From Cross’s 1982 “Designerly ways of knowing” (pdf):

From the RCA [Royal College of Arts] report, the following conclusions can be drawn on the nature of ‘Design with a capital D’:

- The central concern of Design is ‘the conception and realisation of new things’.

- It encompasses the appreciation of ‘material culture’ and the application of ‘the arts of planning, inventing, making and doing’.

- At its core is the ‘language’ of ‘modelling’; it is possible to develop students’ aptitudes in this ‘language’, equivalent to aptitudes in the ‘language’ of the sciences – numeracy – and the ‘language’ of humanities – literacy.

- Design has its own distinct ‘things to know, ways of knowing them, and ways of finding out about them’.

I identified five aspects of designerly ways of knowing:

- Designers tackle ‘ill-defined’ problems

- Their mode of problem-solving is ‘solution-focussed’

- Their mode of thinking is ‘constructive’

- They use ‘codes’ that translate abstract requirements into concrete objects.

- They use these codes to both ‘read’ and ‘write’ in ‘object language’.

From these ways of knowing I drew three main areas of justification for design in general education:

- Design develops innate abilities in solving real- world, ill-defined problems.

- Design sustains cognitive development in the concrete/iconic modes of cognition.

- Design offers opportunities for development of a wide range of abilities in nonverbal thought and communication.

From a 2009 interview in Rotman Magazine:

How can design thinking help managers tackle ‘wicked’ problems?

Part of the difficulty in dealing with wicked problems is you don’t know when you’ve got the right solution. There’s no definitive, correct solution, and there’s no definitive, correct view of the problem. They’re called wicked problems because they haven’t been tamed; they haven’t been structured or well-defined; they’re not cut and dried; and they don’t yield readily to a single optimal solution. This is an important point because much of training in management and reasoning is about finding the ‘right’ solution. In dealing with wicked problems, it’s not about optimizing, it’s about ‘satisficing’, as Herbert Simon describes it in his book The Sciences of the Artificial. Simon, himself greatly accomplished in science and economics, realized that when faced with these sorts of intractable problems, you can’t actually optimize a solution, but rather find one that is satisfactory.

Another thing we’ve realized about these wicked problems is that the problem and the solution have to be – and indeed do – develop together. The understanding of the problem begins to develop as soon as you try to develop ideas as to how you’re going to solve it. It’s a mistake to set out what the problem is first and then try to find a solution. Be prepared for the fact that the problem and the solution will co-evolve, and you’re going to go to and fro between the two of them.

The final point about wicked problems is that constructive or design thinking is indeed the best way to tackle them.

Thoughts on design as a “third culture” or on this table?

[Update: see also — Bela Banathy: Salient attributes of the designer.]

Thanks Howard! This is very helpful, especially at the moment as I am writing up a ‘landscape’ of current thinking/approaches in research to climate change engagement work. I am arguing that design thinking is fast emerging as a viable ‘mode’ and way of framing the issues. So this is very helpful. I may ask if you would be willing to share your graphic with me.

Renee

Glad to be of help, Renee.

Interesting post. I noted that all three ways of knowing reflect western European worldviews. A fourth culture worth considering is aboriginal ways of knowing, especially North American aboriginal ways of knowing. In my inquiry into this topic, I’ve come to think that the holistic worldview of aboriginal peoples holds promise for solving wicked problems.

We tend to look at the parts (in science, humanities and design). The aboriginal worldview tends to look first at the whole. You might want to start here: http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/curriculum/Articles/BarnhardtKawagley/EIP.html

Good luck!

Hi Angie, just looking back at this post and realized i never responded to your comment. Sorry for that, and a belated thanks.

I’m thinking that if it makes sense to talk about a “design turn” that is part of a broader “practice turn,” aimed reviving engaged appreciation for Aristotle’s praxis, then theoria, poiesis, and praxis together comprise a cultural way of knowing, akin to that which another culture (e.g. aboriginal) has developed. Thanks for the link!

Howard–

Charles Correas says:

…the traditional persona of the architect [is] an activist who is, first and foremost, a compulsive problem-solver. This is in sharp contrast, to, say, a sociologist or historian–who tends to be a relatively passive observer of events. The differences between these disciplines start right from earliest training. For if the architect freshman cannot come up with a design at the end of a semester because he “doesn’t have enough data” . . . well, he flunks. And, of course, the exact opposite happens to the student of history or sociology. If he comes up at the end of the semester with a new theory based on insufficient data, then he flunks.

Thus from Day 1, each discipline nurtures quite a different set of instincts.

Hi Carrie! Just looking back at this post and realized i never responded. My apologies. That’s a hilarious comparison C. Correas makes. Thanks.