“Thirty years from now the big university campuses will be relics,” declared management guru Peter Drucker in a 1997 Forbes article.

Here’s some more recent commentary.

“How Disruptive Innovation Can Deliver Quality and Affordability to Postsecondary Education,” a report by Clayton Christensen and colleagues, partnering with the Center for American Progress (pdf):

Disruption hasn’t historically been possible in higher education because there hasn’t been an upwardly scalable technology driver available. Yet online learning changes this. Disruption is usually underway when the leading companies in an industry are in financial crisis, even while entrants at the “low end” of the industry are growing rapidly and profitably. This is currently underway in higher education.

“Who Takes MOOCs?” by Steve Kolowich in Inside Higher Ed:

The broadest and most easily comparable data that both companies were able to share had to do with geography. Across all Coursera courses, 74 percent of registrants reside outside the United States. (The biggest foreign markets have been Brazil, Britain, India and Russia, according to Ng.) At Udacity, “a great majority” of the students registered for its six current courses live abroad, according to Stavens, who could not immediately provide exact figures.

“Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit From Free Courses” by Jeffrey Young in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

The contract reveals that even Coursera isn’t yet sure how it will bring in revenue. A section at the end of the agreement, titled ‘Possible Company Monetization Strategies,’ lists eight potential business models, including having companies sponsor courses.

“The Future of Higher Education,” a report and from the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center:

[We] asked digital stakeholders to weigh two scenarios for 2020. One posited substantial change and the other projected only modest change in higher education. Some 1,021 experts and stakeholders responded.

39% agreed with a scenario that articulated modest change by the end of the decade:

In 2020, higher education will not be much different from the way it is today. While people will be accessing more resources in classrooms through the use of large screens, teleconferencing, and personal wireless smart devices, most universities will mostly require in-person, on-campus attendance of students most of the time at courses featuring a lot of traditional lectures. Most universities’ assessment of learning and their requirements for graduation will be about the same as they are now.

60% agreed with a scenario outlining more change:

By 2020, higher education will be quite different from the way it is today. There will be mass adoption of teleconferencing and distance learning to leverage expert resources. Significant numbers of learning activities will move to individualized, just-in-time learning approaches. There will be a transition to “hybrid” classes that combine online learning components with less-frequent on-campus, in-person class meetings. Most universities’ assessment of learning will take into account more individually-oriented outcomes and capacities that are relevant to subject mastery. Requirements for graduation will be significantly shifted to customized outcomes.

“Researching Online Education,” from Union Square Ventures (USV):

The work led us to a few hypotheses:

- We’re skeptical a business model that charges for content will work at scale and in the long run.

- We expect education platforms that offer vertical content and/or specific education experiences will be more successful than horizontal platforms, though we think credentials and careers offer two opportunities for horizontal aggregation

- Without credentialing or careers, online education seems aspirational and removed from the day-to-day of many people.

The USV research was followed by some sharp discussion:

Blake Jennelle: If you assume #1-3, it sounds like the winners in online education might themselves be schools. …

Fred Wilson: For sure. But schools of a different sort. Codecademy is a school. Duolingo is a school.

Blake Jennelle: Yes exactly. And Khan Academy isn’t a school.

Jeffrey McManus: Schools have instructors. Those are web apps. They’re more akin to books in that respect.

Fred Wilson: Why do schools have to have instructors?

Marco Fisbhen: They don’t have to, but to ignore the power of great teachers is to ignore the impact of great storytelling. The best teachers engage the students in a way that’s hard for technology to emulate. Perhaps when it comes to coding (or STEM in general) technology does the job of “teaching” the subjects in a “hands-on” approach. But do you believe that a “codecademy” delivery is possible for literature? History? I’m honestly asking the question. I’m not 100% sure of the answer.

Fred Wilson: i think teachers are the most important thing in the education system. but i just don’t buy that schools have to have them.

Blake Jennelle: Maybe the essence of a school is a “community of learners.” Always teaching but not always teachers…

Fred Wilson: Yesssssss

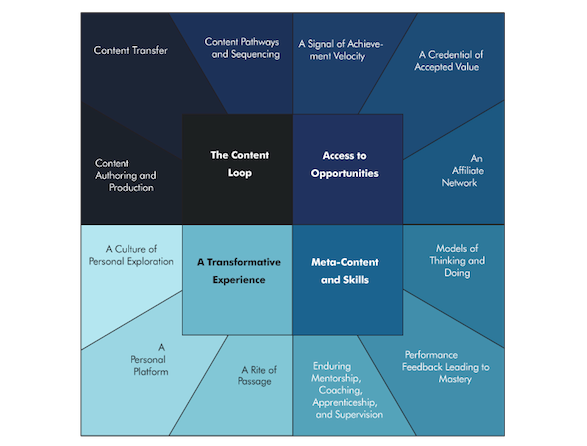

Colleges offer more than just lessons. A degree. A network. An experience. The idea of “unbundling education” is that these value propositions might be disaggregated. Here’s a visualization by Michael Staton, whose draft paper on the topic is published by the American Enterprise Institute (pdf):