What is systems thinking? — the act of thinking itself, separate from other ways we might approach systems?

“[I] set out to clarify the construct of systems thinking,” writes educational theorist Derek Cabrera in his 2006 dissertation (pdf), “and to define it as a conceptual framework apart from systems science, systems theory, systems methods, and other perceived synonyms.”

Cabrera’s approach takes systems thinking as a “cognitive endeavor,” and distinguishes it from “knowledge-about-systems.”

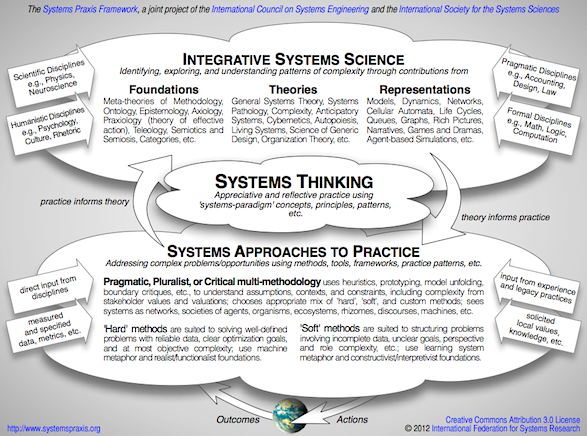

Compare this approach, for example, with the recent “system praxis framework” diagram, developed by the International Council on Systems Engineering and the International Society for the Systems Sciences, which describes systems thinking as a “practice,” rather than a cognitive act. Is Cabrera’s insistence on a thinking-practice distinction helpful?

The gist of his clarification is this: “Recent work in systems thinking describes it as an emergent property of four simple conceptual patterns (rules),” he and coauthors Laura Colosi and Claire Lobdell write in a 2008 paper (“Systems thinking”), published in Evaluation and Program Planning.

The four conceptual patterns are: distinctions, systems, relationships, and perspectives (DSRP). If information is “what to know,” DSRP is “how to know,” describes Colosi in an online video.

The story of how Cabrera came to the DSRP formulation is itself intriguing. Seeking a pattern of connections across the “tangled overgrowth” of systems literature, Cabrera examined three vast compendiums: the 2003 four-volume set of 76 canonical papers (Systems Thinking) edited by Gerald Midgley, the 2004 International Encyclopedia of Systems and Cybernetics edited by Charles Francois, and the dense 2001 visual map (Some Streams of Systemic Thought pdf), developed by Eric Schwarz and the International Institute for General Systems Studies. Among these, DSRP was “hidden in plain sight,” he and Colosi write in their new book, Thinking at Every Desk: Four Simple Skills to Transform Your Classroom.

The DSRP framework is illustrated by the questions:

- Distinctions (identity and other): What is __? What is not __?

- Systems (part and whole): Does __ have parts? Can you think of __ as a part?

- Relationships (inter and action): Is __ related to __? Can you think of __ as a relationship?

- Perspectives (point and view): From the perspective of __, [insert question]? Can you think about __ from a different perspective?

The 2008 paper was accompanied by some glowing responses: Deborah Wasserman called it a “gift,” Branda Nowell “significant and innovative,” and Lois-ellin Datta “a sort of Unified Field Theory of Systems Thinking.” References to DSRP on the popular Systems Thinking World Linkedin group are also complimentary.

In the book Thinking at Every Desk, Cabrera and Colosi extend the claims for DSRP. Whereas in the 2008 paper, they presented DSRP as a set of processing rules for systems thinking; in the new book, they describe it as a set of universal structures for six types of thinking: critical, creative, interdisciplinary, scientific, systems, and prosocial. In the 2008 paper, they theorized the emergence of concepts from the interaction of content (information) and context (the DSRP processing rules), i.e., concepts = content + context. In the new book, this formula has become: knowledge = information x thinking (DSRP).

A host of questions arise. Could the development of all these types of thinking really be this clear-cut? How does this understanding of “prosocial” thinking relate to, say, the normative and interpersonal competences described by Arnim Wiek and coauthors? How might divergent attributions of knowledge be accommodated or reconciled — this being a frequent goal of the systems practices sidestepped by Cabrera and colleagues?

Responding to the 2008 paper, Gerald Midgley (in “Is there gold at the end of the rainbow?”) wondered if Cabrera and coauthors had come too close to a constructivist view of meaning:

Consider how this work on systems thinking relates to the practice of biophysical science. I believe that, like my own work on systemic intervention (Midgley, 2000), all the D, S, R, and P concepts are directly relevant; their explicitly adoption in scientific methodologies would do a great deal to enhance the critical practice of science. Nevertheless, by framing inquiry in terms of the construction of meaning (conceptualization), there is a danger that scientists will claim that this undermines any talk of biophysical reality. Is there further theoretical work that can be undertaken, perhaps drawing upon pluralist philosophies of science (e.g., Cartwright, 1999) or systems approaches that have sought to welcome scientific methods (e.g., Midgley, 2000; Mingers, 2006)?

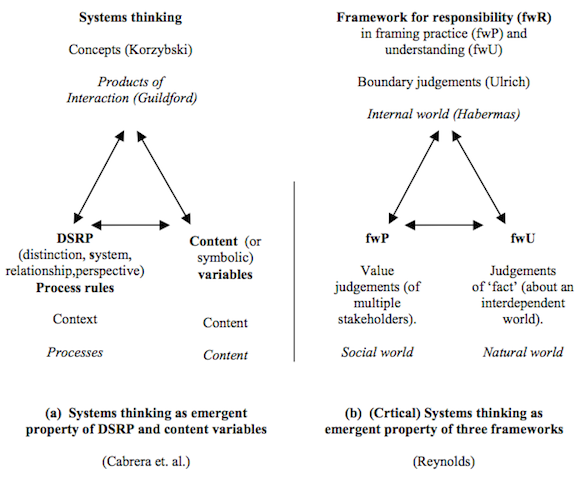

And Martin Reynolds (in “Systems thinking from a critical systems perspective”) developed a figure to compare Cabrera and coauthors’ concept of systems thinking with his framework for responsibility:

Much to ponder.

In any event and theoretical considerations aside, kudos to Cabrera and colleagues for their leadership on much-needed educational reform.

Here is the website for Thinking at Every Desk, and below is Derek Cabrera’s October 2011 talk at TEDx Williamsport.

excellent