The shortcomings of education-as-usual prompt the question: What is education for?

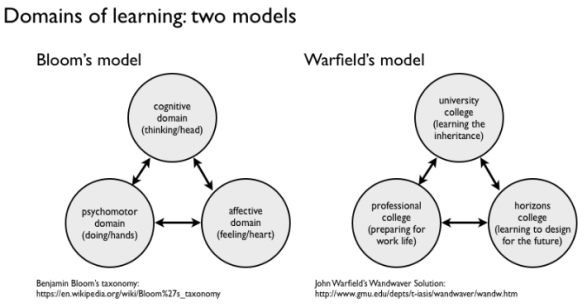

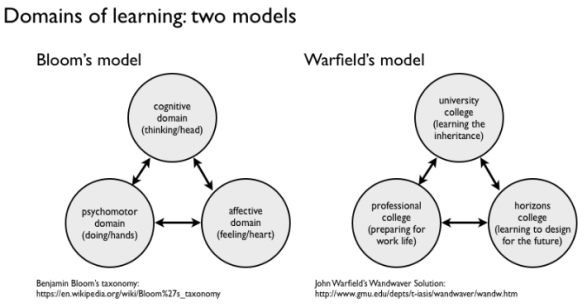

When this topic comes up, listen for mental models. Sometimes, explicitly or not, commentators and critics will describe a version of Bloom’s taxonomy: learning as cognitive, affective, and psychomotor — learning, that is, for the head, heart, and hands.

Last year, David Brooks reached for Bloom’s model, or a version of it, in commenting on the popular “excellent sheep” essay, now book, by William Deresiewicz. This past Sunday, Deresiewicz invoked the model in a scathing assessment of higher education, delivered at the PNCA Critical Theory and Creative Research commencement.

My interest here is not in Deresiewicz’s critique, courageous and welcome though it certainly is, but rather in the model itself. Higher education, Deresiewicz laments, has become centered around a commercial focus (i.e., hands, in this version), to the diminishment of critical thinking (i.e., head) and abdication of responsibility for self, soul, meaning, and purpose (i.e., heart).

Bloom’s model is a touchstone of mine as well. That said, any model affords only a partial view of a complex situation. So as intuitive, informative, and salient as a Bloom-based approach may be, it’s worth looking around for complementary ones. In other words: What models might inform how one understands the successes and failures, challenges and opportunities of contemporary higher education?

One that comes to mind is John Warfield’s, which he called The Wandwaver Solution, and which I’ve reproduced at top, alongside a simplified version of Bloom’s. While I labeled this figure “domains of learning,” the word “domain” is used differently in each of these two models. Bloom’s distinctions are drawn around three bodily ways of learning in the human organism, Warfield’s around areas and approaches about and through which we might learn.

Warfield described his 1996 Wandwaver proposal as “an unbudgeted plan for revolutionary change in the university.” He envisioned university structures and curricula redesigned around colleges of past, present, and future: a University College (learning about the inheritance), a Professional College (preparing for work life), and a Horizons College (learning to design for the future).

This latter, the Horizons College, is of course the most novel aspect of Warfield’s sketch proposal, much of which remains unspecified and open to interpretation.

Interpretively, then: What might be the benefits of a Wandwaver-style university structure? I’ll posit three interconnected ones, imagining the three colleges as tightly linked:

- Enacting the human project: The structure of the university is designed to mimic and facilitate the temporal accretion of human knowledge — the processes whereby the “inheritance” is sustained and re-examined.

- Fiercely relevant: Concurrently, the design is future oriented, contextual, focused on horizons of concern or opportunity.

- Purposeful: A reflecting-on-the-past-while-designing-for-the-future curricula might well afford the types of “mind-expanding, soul-enriching” experiences that William Deresiewicz champions.

Thoughts?

H/t to Stuart Umpleby, from whose 2014 International Society for the Systems Sciences talk I first learned of the Wandwaver proposal.

John Warfield, who passed in 2009, synthesized his thinking in 2006’s An Introduction to Systems Science.

Update: Bill Deresiewicz has a new essay, “The Neoliberal Arts,” published in Harper’s today.

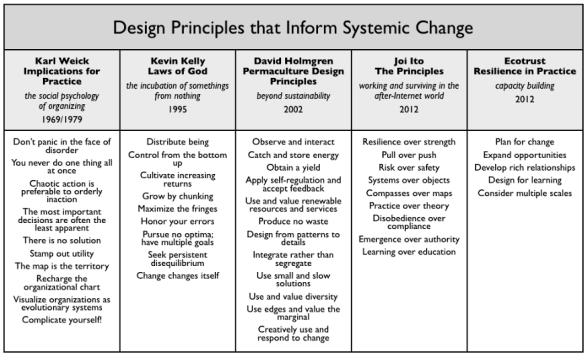

Back in 2015 and ’16, Peter Tuddenham sparked a variety of conversations about systems literacy.

Back in 2015 and ’16, Peter Tuddenham sparked a variety of conversations about systems literacy.